Overwhelm in a Time of Political Strain

What it is, how it develops, and why it's the hinge between chronic stress and burnout.

📌If you find this work of value, and want to help your neighbours find their way to it, please like, comment, and share this post. Each of these small actions helps the algorithm place this post in front of others who may need it.

Dear friends

Before we begin, a quick note: this isn’t one of my ‘usual’ Sunday posts. It has been a tender and difficult week here as our community prepared to say goodbye to my father-in-law, and my attention has naturally been with my family. I’m grateful for your continued patience, and now that we have celebrated John’s life, I hope to settle back into my usual rhythm in the coming days.

I’ve spent the past few weeks writing about how chronic political stress takes hold, and how it affects both mind and body. I began by explaining why burnout cannot be understood only as a workplace issue.

I then outlined the ways in which it drains our ability to stay politically engaged.

After that, we looked at the difference between acute and chronic political stress, and I described the mental and emotional effects that build over time.

And in my last post, I turned to the physical impact and showed how the slow weakening of democratic norms can affect almost every bodily system.

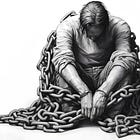

Before we move on to burnout itself, there’s a stage in between that needs its own space. I wrote about it some months ago in a more general sense — and shared three fast-acting tools to help you tackle it — but I didn’t address what it is, how it arises, or what happens when we don’t tackle it. In the context of political burnout, this matters, because it’s the point where chronic stress begins to tip into a state we can no longer recover from easily. That transitional state is overwhelm.

Overwhelm is not simply an intensification of stress, and nor is it defined by a particular set of symptoms. It is what happens when our internal resources can no longer keep pace with the demands made of us — the gap between what is asked of us and what we have available to give becomes too wide. We can still function, but we feel as though we’re hanging on by our fingertips rather than functioning as our whole self.

When chronic stress stays within the limits of what our bodies and minds can handle, rest, boundaries, and support can still give us enough stability to recover. Overwhelm marks the point at which that balance starts to fail. When the demands placed on us exceed our capacity, the processes that once adjusted to pressure can no longer keep up. That shift becomes functional rather than emotional. This is the moment when the nervous system begins to lose its usual flexibility and shifts into conserving resources rather than distributing them freely.

To understand how burnout develops under authoritarian conditions, we need to understand how overwhelm is produced, because overwhelm acts as the catalyst that changes how stress behaves. Under sustained political pressure, it accelerates the shift from what might be considered manageable strain into territory that begins to wear us down.

Chronic political stress develops over time, growing as institutions become less stable, as political events speed up, and as the consequences of those events land directly and repeatedly in everyday life. Most of us can cope with this at first, but when that steady pressure is met with a wider climate that pushes our internal systems beyond what they can absorb, overwhelm sets in.

That wider environment does not evolve by chance. Authoritarian systems deliberately create a sense of constant pressure. They do this through uncertainty, mixed messages, too much information to process, and the slow breakdown of trust. In an environment where the amount and pace of information rise beyond what anyone can reasonably handle, chronic political stress swiftly becomes overwhelm.

Political updates, legal manoeuvres, policy changes, court rulings, and sudden shifts in public behaviour build up at a pace that gives us no time to take in what is happening. Disinformation adds to the load by scattering the facts, leaving us to work out what is real rather than simply understand events. We end up spending more time separating truth from distortion than making sense of the developments themselves. This confusion is not accidental. It increases the pressure by pulling our attention away from thoughtful action and towards constant monitoring.

Uncertainty plays a similar role. Decisions are announced and then reversed, and we see public messages that do not line up, and statements that leave key details unclear. Rules can also change with almost no warning. When all of this happens at once, it creates a level of unpredictability that leaves many of us feeling unsteady, because we cannot judge with confidence what will come next. Living in this kind of uncertainty places a steady strain on the nervous system.

Bureaucratic pressure grows as administrative processes become slower or harder to move through. Tasks that used to be straightforward need extra steps, and public services work with less consistency than they once did. Each interaction takes more time and more energy, and carries a small degree of uncertainty. On their own, these changes are manageable, but taken together they create an environment in which almost everything demands more from us than it used to.

There is also a psychological layer to this pressure, and we can see it clearly in the United States today. Layered messaging that suggests resistance is pointless, that those in power are firmly in control, or that support will not come has become part of the political language. The steady stream of threats, promises of punishment, and claims that long-standing institutions cannot be trusted reduces our sense of safety and agency. Over time, these signals create a feeling of collective vulnerability and raise understandable doubts about whether individual or community action still matters. Those doubts then sit alongside the wider pressures, increasing the overall strain.

Overwhelm develops from the way these pressures combine. It is not the same as being busy or stretched thin. It is the point at which our ability to organise ourselves, to steady our responses, and to make sense of what is happening starts to weaken. Instead of adjusting as we once could, our bodies and minds move into a more guarded state. Our capacity to focus becomes less reliable because our attention has already been pushed too far. Information becomes harder to absorb simply because there is too much of it. When this happens, many of us step back from engagement not because we no longer care, but because the amount of input has gone beyond what we can reasonably process.

Once overwhelm takes hold, burnout follows more quickly. The processes that usually help us recover from stress become less dependable, and our capacity for reflection and planning begins to fade. We find ourselves reacting rather than responding, often swinging between pushing too hard and withdrawing altogether. Our sense of efficacy shifts as well. When events move faster than we can keep up with, it becomes difficult to believe that our actions matter — and that loss of confidence lies at the heart of burnout.

This is why overwhelm is not a personal failure but a predictable political outcome shaped by the environment we are living in. We are affected not because we lack resilience, but because no one is designed to cope with constant uncertainty, unfiltered information, and deliberate instability. Overwhelm is now part of the pressure machinery used by authoritarian regimes to weaken collective resistance. It undermines our ability to think clearly, organise well, and stay engaged over time.

But recognising overwhelm for what it is gives us the chance to step in early. It helps us understand why ordinary days can feel unusually heavy, why our attention drifts, and why some days our energy drops even when nothing out of the ordinary has happened. And it reminds us that the issue is not personal inadequacy, but the cumulative weight of pressures designed to stretch people beyond what anyone can reasonably carry.

I know the terrain of overwhelm well. I live with a chronic illness in which both my nervous system and my immune system stay highly activated even on ordinary days — I can’t afford for that response to intensify. This is one of the reasons why I’ve spent the past twenty-five years studying and practising nervous system regulation. I’ve shared the practices I rely on to stay calm and grounded in the series In Uncertain Times, This Is Where You Start. Please don’t underestimate how powerful the practice of Ujjayi breath is — I can steady myself in seconds, no matter what’s going on around me.

As our use of technology has increased, I’ve now come to understand information as our quickest route to overwhelm. I’ve had to develop a structured way of managing what I take in while still keeping up with events in the world. Because my ability to function day to day depends on this, what I’ve developed goes well beyond anything you might find in a quick online search. I had planned to share these methods later, once I had taken you through burnout itself, but feedback from several readers has shown me that many of you cannot wait. It has made me realise that the approaches I now take for granted are of immediate help to anyone trying to stay steady in the middle of everything unfolding around us. So while we move through burnout, I’m going to walk you through the steps I use to make my information load lighter and more manageable. I will be publishing these as I write them — if you have not yet subscribed, you may want to so you do not miss a post.

Overwhelm is the point at which chronic stress begins to turn into burnout. It is the moment when the demands placed on us start to exceed what we can reasonably sustain. Understanding this shift matters, because this is where we still have the most room to support ourselves and one another. When we recognise overwhelm early, we give ourselves the best chance of staying steady and keeping our resistance strong.

In solidarity, as ever

— Lori

© Lori Corbet Mann, 2025

If anything here rang true for you, I’d like to hear about it— what stood out, or felt familiar to you?

If this post was useful, and you know someone else who’s finding things heavy-going at the moment, please feel free to share it with them.

And if you’d like to follow the steps I use to make my information load lighter and more manageable, you can subscribe here:

The pace of updates and the constant reading and deleting emails throughout the day, intermittently, has become a habit, bordering on addiction. With phone at the ready, I find myself constantly thinking I may have "missed something." This disruption of normal day to day functioning has the effect of wasting too much time throughout the day. The result being feeliing a bit "on edge" and thinking "where has my day gone?" Wasting days...months...years...in a blur of constant information.

Friday, a songwriter died,

A lifetime of pain,

Trump’s greed ended Todd Snider.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/todd-snider-country-singer-death_n_6918b1a9e4b0191be9d554bd?origin=home-zone-b-unit

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lori, I'm sorry, but this was really hard for me, specifically because it was so easily avoidable. Todd Snider deserved a better end after a lifetime of pain and diminishing hope, yet while still giving so much to the world around him, even through a lifetime of unrelenting pain from spine damage.

A medicine available since before man existed, ruined by American greed and brutality, took almost 1M innocent American lives, and now Todd's. Even the haiku form fails to make any aspect of this loss any more acceptable. If I could have just stood beside him for a moment I could likely have helped him...at least this time. But he was alone in his lost hope, and we all know just how that feels.

I'm going to try to focus on his music, not his tragic end as the result of being one of countless millions of Americans which Trump and RFK, JR consider to not be "strong enough to survive".

Are any of us that strong? I think we can prove that we are by planning a parade of celebration to be held in every American city and town on the yet unknown Day of Liberation from disunity and fear, hate and ignorance, distrust and violent intent.

I have little doubt that I WILL be there on that day to yell and cry and laugh and hug, hug, hug EVERYONE in sight!

Thank you, Lori. I feel a bit better now.