In Uncertain Times, This Is Where You Start — Part 4

Safe-guarding your nervous system is critical. This post teaches how to extend diaphragmatic breathing, deepening calm.

Hello friends

In my last post in this series, I walked you through diaphragmatic breathing — the foundational practice for calming an overloaded nervous system, and resetting your internal state through the physical mechanics of the body itself. I mentioned that when you breathe deeply using the diaphragm, you begin to activate the parasympathetic nervous system — the part that signals that you’re safe to slow down now.

But here’s something important that’s worth repeating: it’s not the inhalation that does the calming, but the exhalation. A long, slow, steady exhalation is what truly switches gears in your nervous system, sending a powerful and unmistakable message that you're safe to downshift.

And if you're going to extend the exhalation, you first need to have a good supply of air (well, it's mainly carbon dioxide by this point, but let’s not get pedantic) to exhale. You need a full, complete breath in — not a chesty suck of air, nor even a belly breath — but a deep, spacious inhalation that fills your lungs from bottom to top.

That’s where this next practice comes in.

What We’ll Cover Today:

Fuller Breath, Deeper Benefits

How to Practise Three-Part Breath

Why This Matters Now

Fuller Breath, Deeper Benefits

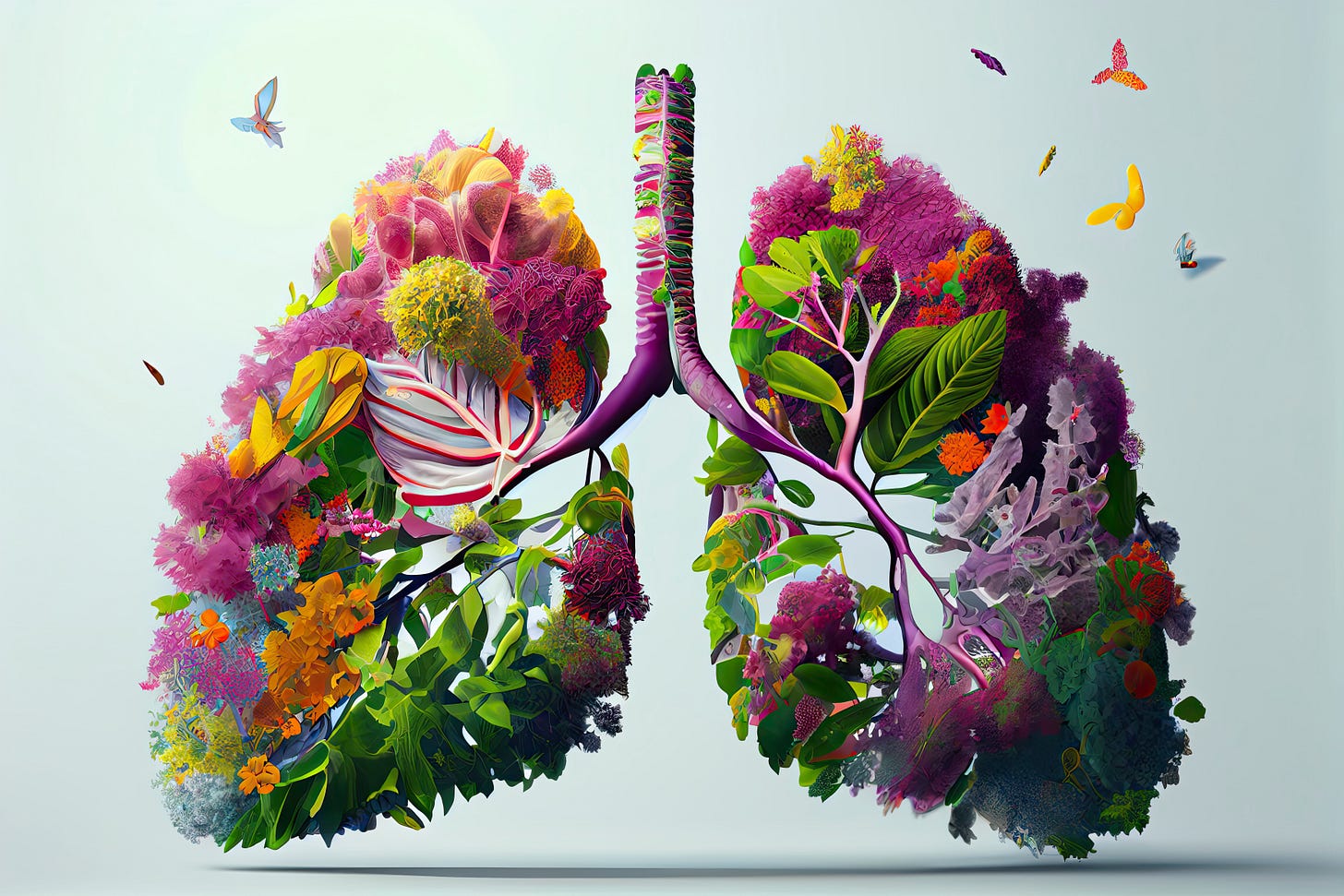

It’s called Three-Part Breath, and it’s exactly what it sounds like: a conscious, progressive inhalation filling all three lobes of your lungs — lower, middle, and upper — followed by a long, gentle exhalation. It helps you build up the capacity of your lungs without forcing it, and in doing so, it makes those long, nervous-system-soothing exhalations possible.

Before we move into the practice itself, it’s worth knowing that the benefits of breathing this way go far beyond calming the nervous system.

With every-day chest breathing — especially under stress — we often use just a fraction of our lung capacity. A typical shallow breath moves around half a litre of air, mostly into the middle and upper lobes. When you start breathing diaphragmatically, you can increase that to two litres or more. And with three-part breath — where you consciously expand the lower, middle, and upper sections of the lungs in sequence — you’re using the full capacity of the lungs.

The benefits of this kind of 'full-body' breathing extend way beyond helping you feel calm. When your breath is shallow, the lower lobes of your lungs — where the majority of your alveoli (the little air sacs where gas exchange happens) are located — don’t get fully ventilated. This leaves behind residual air, which contains less oxygen and more carbon dioxide. It’s not dangerous per se, but over time, consistently shallow breathing can reduce the efficiency of oxygen exchange and contribute to feelings of fatigue, brain fog, and even low-grade inflammation. Diaphragmatic breathing and three-part breath help you clear out that stale, stagnant air.

It also boosts oxygen intake, which means more oxygen is delivered to your brain, muscles, and organs — supporting clearer thinking, steadier energy, and improved physical resilience. It increases lung elasticity and capacity over time, which makes every breath more efficient. You're also supporting your cardiovascular system, because the two are intimately linked. The more efficiently your lungs can bring in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide, the less strain there is on your heart to deliver oxygenated blood around the body. And it supports better waste removal, which can subtly shift everything from your mental clarity to your immune response.

So yes, breathing like this will help you stay grounded and calm, but it’s also training your body to breathe in a way that supports vitality and stamina, right down to the cellular level.

Let’s begin.

How to Practise Three-Part Breath

As with diaphragmatic breathing, you will probably find it easiest to start this practice lying down. Let your body rest fully, arms relaxed by your sides or gently placed on your torso to help guide your awareness.

Close your eyes if that helps you focus inward. Begin by noticing your natural breath. Don’t change anything yet — just observe.

Then, slowly begin to shape the inhale into three distinct phases.

First, inhale into your lower lungs. Let your belly rise, just as you practised in diaphragmatic breathing. Feel the breath move down and outward, expanding the abdomen.

Next, without pausing, continue the inhale into the middle lungs. Let your lower ribs widen, feeling them spread outward to the sides like a pair of wings opening.

Finally, top up the breath into the upper chest. Feel your collarbones gently lift — not straining, just allowing a small rise.

Now exhale — slowly, steadily, smoothly — through your nose. Let the breath leave in a single, continuous wave. Try not to force it out, just stay with the sensation of soft release, from top to bottom.

Pause for a moment at the end of the exhale. Not by holding your breath, but by letting it settle before the next inhale begins.

Then repeat.

Start slowly. At first, breathing this fully might feel uncomfortable or even a little unsettling. If you’re used to breathing high and shallow — especially common when we feel anxious — filling the lungs from bottom to top can create a sensation of exposure or vulnerability. That’s okay, there's nothing to be afraid of. You’re safe, and you're not doing it wrong. You’re just giving your body a new experience, and it may take a little time to settle into it.

The goal isn’t to force the lungs to expand fully, but to invite the breath into new spaces, gently and with patience. With time, you’ll begin to notice how much more air your body can take in, and how much more ease you feel in the exhale.

Why This Matters Now

Three-part breath trains your body to use the full capacity of your lungs. And when you have more air in the system, you can slow the exhale down without strain —creating the conditions your nervous system needs to switch off the alarm bells.

Even more than that, it teaches you presence. Each part of the breath becomes an anchor, helping to bring your awareness into the now rather than worrying about what the future may hold — one inhale, one exhale at a time.

Try practising this for a few minutes a day, maybe just after your diaphragmatic breathing. You don’t have to be perfect. You just have to show up, breath by breath, and let your system remember what steadiness feels like.

In my next 'breathing' post, we’ll begin to work with the most potent breathing practice I know — one that takes this calm and deepens it even further. In the meantime, please keep practicing, using your chosen oils where possible. You’re building a strong foundation to get you through the months ahead.

—Lori

© Lori Corbet Mann, 2025

This post is fourth in a series, each of which builds on the practices contained in the posts before. If you've missed any of the others you can find them here:

Hi Lori,

I've been thinking about one of your previous articles about staying out of sight. Does that include leaving Substack? As far as deleting old posts, how can one possibly delete all of one's comments and likes/❤️ on here? I obviously would have to delete this account and start a new one with a pseudonym, unless Substack let's you change your name... 🤔

Thank you for writing these articles. These are so good. I am forwarding them to friends and family. Breath is the anchor. Getting that right, makes a difference. It's the nervous system that calms you. I believe we have that ability as young children, but we aren't trained or encouraged to be aware of what it does for us. And once it's diminished, it makes us vulnerable to fear. It takes courage to restore it. Thank you Lori.

The best definition of courage I've ever heard was: being afraid and doing it anyway.

We all need to do this!