The Mind Under Siege: Chronic Stress in Authoritarian Times

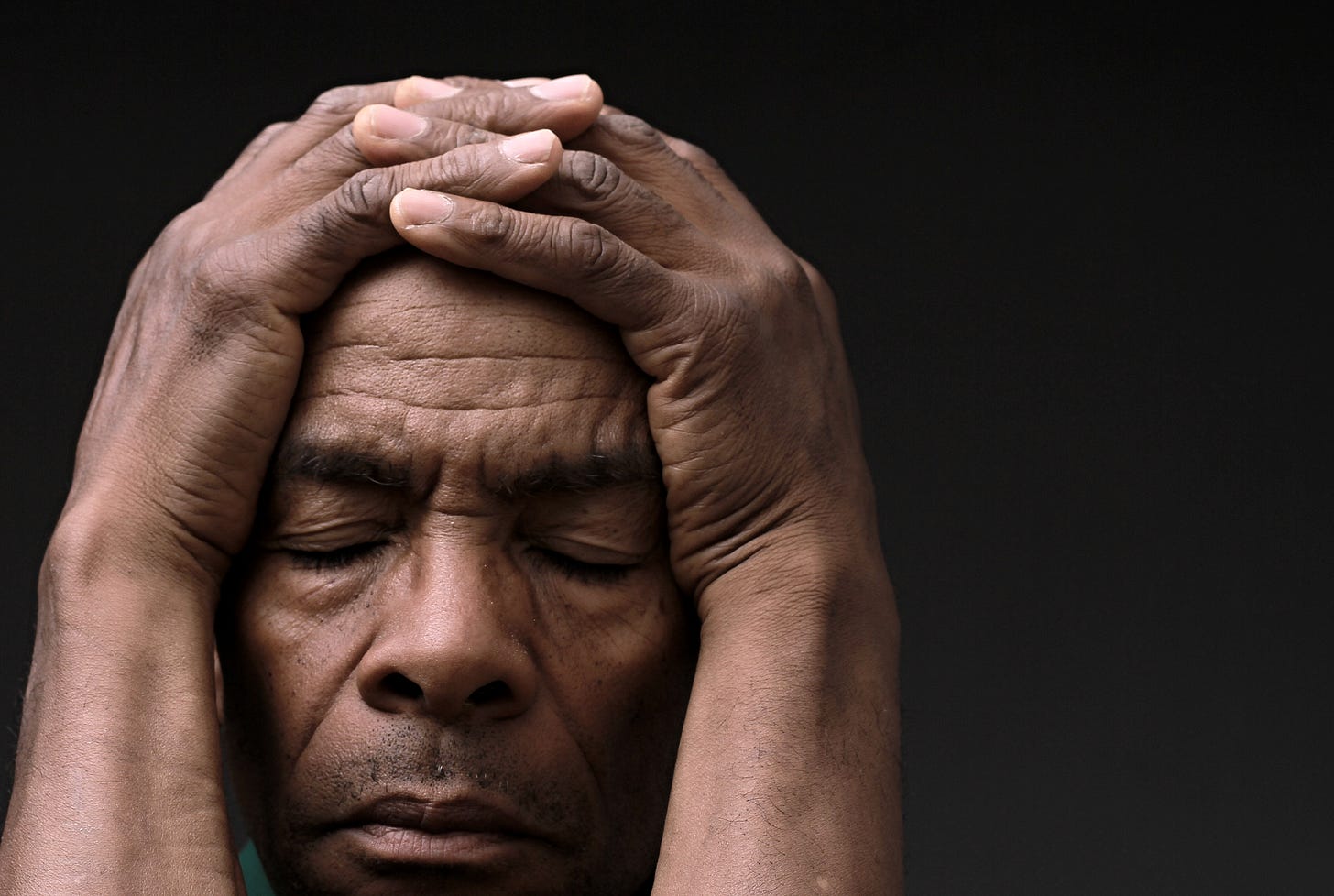

Tracing the emotional and cognitive fallout of unrelieved political pressure.

📌The full post is free for everyone to read — only the downloadable checklist is reserved for premium subscribers.

If you find this work of value, and want to help your civic neighbours find their way to it, please like, comment, and share this post. Each of these small actions helps the algorithm place this post in front of others who may need it.

Dear friends

In my opening post on political burnout (which you can read here if you missed it), I mentioned that psychologists and health specialists have argued about burnout for over fifty years. But there is one thing on which all burnout researchers agree: it is not an isolated phenomenon. It is the outcome of a process that begins much earlier, with the way our bodies and minds respond to stress.

Burnout grows from prolonged, unresolved stress. In workplaces, this pattern has been studied for decades, but in political activism — especially under authoritarian pressure — it has not. Yet the mechanisms are the same. When we live in a climate of unrelieved stress, our path to exhaustion, cynicism, and withdrawal is set.

So, if we are to understand how we may be at risk of burnout under advancing authoritarianism, we first need to understand stress itself. Without this foundation, we are not likely to recognise political burnout when it shows up, and may instead think of it as a personal weakness, or a passing phase. With it, however, we can see the structure more clearly: how stress is built into our survival, how it functions well within boundaries, and how it corrodes when it becomes the permanent backdrop to our lives.

Acute Stress

Acute stress is your body’s immediate response to a perceived challenge, threat, or demand. In daily life, it’s what happens when you narrowly avoid a car accident, when you are suddenly called to present in a meeting, or when your child screams from the next room. We call these events “stressors” because your brain detects potential danger and instantly activates your stress response.

The hypothalamus — a control centre deep in your brain — signals your adrenal glands to release adrenaline and cortisol. Your heart rate rises, breathing quickens, and blood shifts away from your stomach toward your muscles. Your senses sharpen and your attention narrows onto the source of the threat. This is the classic “fight, flight, or freeze” response. You may experience it as a rush of energy, a tightness in the chest or stomach, or a racing mind that leaves no room for anything else.

When we’re facing the erosion of democratic norms, acute stress comes from sudden, high-intensity moments that jolt both your mind and body. It might strike the instant election results flash across your screen, when a breaking news headline signals a new crackdown, or when an unexpected court ruling undermines hard-won protections. It can come with the shock of seeing misinformation take off online, or hearing that a trusted ally has been targeted.

These moments trigger the same surge of adrenaline as any immediate threat: your body tenses, thoughts sharpen, and action feels urgent. The feeling may pass quickly once the situation stabilises — but in the moment, it is unmistakably your body’s alarm system in full swing.

Acute stress is not in itself harmful. It is a survival mechanism designed to mobilise energy for short-term challenges. In fact, many of us perform at our best under a manageable dose — the surge before an exam, a deadline, or a competition. Our bodies are built to return to balance once the challenge passes: heart rate slows, cortisol levels fall, digestion resumes, and the system resets.

The real danger comes when stressors start arriving back-to-back, leaving no space for recovery. When each new wave arrives before the last has fully receded, it leaves your system activated all the time. What was designed as a temporary state begins to operate as your body’s default mode.

That shift — from short bursts to an ongoing condition — is what we call chronic stress.

Chronic Stress

When stress becomes chronic, your body and mind do not fully return to balance after you are exposed to stressors. Instead, your stress response stays active in the background, keeping you perpetually on alert.

One of the first effects is on the quality of your sleep. Cortisol levels should be lowest at night, then rise in the early morning to reach their peak around waking. That daily rise and fall of cortisol is part of your circadian rhythm, which keeps your internal systems in sync with the day–night cycle. When cortisol is lower at night, it allows your body to rest and repair. The early-morning peak then helps you wake up feeling alert, and mobilises energy for the day. When stress keeps cortisol elevated at night, that daily rhythm flattens. Sleep becomes lighter and more fragmented, and your brain misses some of the deep restorative stages. Morning arrives without real recovery, and that lack of rest means you begin the day already lacking alertness and energy.

Your energy then declines further, with the fatigue lingering even when your workload is low. This fatigue feeds directly into how your brain allocates resources. When more of your attention is given to monitoring for possible threats, less is available for sustained focus.

Your working memory — the mental capacity you use to hold and work with information in real time — becomes crowded, and you feel like your thoughts slip just out of reach. Memory falters, not in any big dramatic ways but in small lapses — you misplace items, lose your train of thought, forget routine details. You find it harder to follow complex reasoning, and struggle to keep multiple threads in mind at once. Learning also becomes more challenging — new information doesn’t stick as well, and retaining skills or knowledge requires more effort than before.

On top of this, you may feel uneasy in ways that don’t match the situation in front of you — you worry over small details, double-check tasks that used to feel automatic, or circle back repeatedly to the same thought. At other times, your focus scatters so completely that you jump from one thing to another without finishing anything.

Your ability to make decisions also suffers. Instead of weighing options carefully, you fall back on familiar routines, even if they are not the most effective — or you delay making decisions altogether because the mental effort feels too great.

Emotionally, your patience thins — you become less tolerant and more irritable. Sometimes the pattern runs in the opposite direction — instead of reacting more sharply, you step back sooner than you once would have, withdrawing from situations or responsibilities as a way of conserving what little energy you have.

Alongside this, you may notice a steady undertow of anxiety, or low mood. You may find yourself feeling guilty for saying no to a request, for needing rest, or even for mistakes so small they would not usually trouble you. Your mood may swing without warning — from restlessness that makes it hard for you to settle, to boredom where nothing holds your interest, to apathy where little feels worth the effort.

At the same time, your enjoyment of things that once mattered fades. Your brain’s reward pathways don’t respond as strongly under prolonged pressure, so activities you once found satisfying seem flat. Because the reward is weaker, you’re less inclined to repeat those activities, which further reduces your sense of pleasure in daily life. Even small lifts — a favourite meal, a conversation with a friend, finishing a task — can feel muted, as if the colour has drained from them. Work may lose its sense of purpose, or satisfaction.

Your relationships are affected too. When your energy is low and your mental resources are stretched, it becomes harder to pick up on nuance in conversations. You are more likely to miss signals, to struggle to find the right words, to speak more abruptly than you intended, or to lose patience when differences arise. You can’t readily shift perspective or adapt quickly like you once could. That makes misunderstandings more likely, and it reduces your ability to ease tension when it arises.

Social withdrawal may become your way of conserving energy, but it also cuts you off from support that would otherwise ease your load. Over time, that withdrawal can slip into loneliness — even when you’re in the company of others you feel cut off.

Chronic stress reshapes both your thoughts and your feelings. It reduces mental clarity, weakens memory, blunts focus, and alters your emotional responses. None of this happens dramatically. Over time these gradual shifts add up, until the way you think, feel, and relate to others becomes very different from when you are well-rested and well-supported.

These are the mental and emotional effects of chronic stress — regardless of its origin. Most of us will recognise many of them in our own lives, especially now. That recognition is important. It reminds us that what we feel is not a personal failing but the normal response of a system that’s under prolonged strain. Knowing this, we can begin to restore our sense of agency, by directing our energy away from self-blame and toward recovery, boundaries, and the conditions that make repair possible.

But first we need to better understand the physical toll of chronic stress. Although it’s generally overlooked in favour of the mental and emotional effects, chronic stress affects every cell in our bodies. It’s often the starting point for physical pain, digestive issues, reproductive problems, and deeper systemic breakdowns that quietly shape long-term health. We’ll open this up in Tuesday’s post.

For now, I’ve put together a checklist for premium subscribers — you’ll find it at the end of this newsletter. It’s a simple tool to help each of us notice how chronic stress may be affecting our lives at this stage of Trump’s presidency. The point is not to measure ourselves against a standard, but to pause, take stock, and see clearly where we are. That clarity helps us recognise what needs attention, and it gives us a more solid footing for how we respond. There will also be a companion checklist for premium subscribers in Tuesday’s post, which will be centred on the physical effects of chronic stress.

Providing exclusive resources to premium subscribers is my way of saying thank you for making it possible for me to do this work full time — you ensure this work remains freely available to all. Until midnight tonight, I’m offering a third off the subscription price — locked in for life. If you would like to be sure of receiving every post and every resource in the months ahead — and, at the same time help sustain this work for the wider community — I warmly invite you to become a premium subscriber.

Every subscriber plays a part in sustaining this work. Free and premium subscribers alike can help by liking, commenting, and sharing posts. Each of those small actions helps the algorithm place this work in front of others who may need it.

And whether you choose free or premium, I’m grateful you’re here. Your presence and engagement are what make this work matter.

In solidarity, as ever

— Lori

P.S. If you plan to upgrade to a premium subscription, please use the website rather than the app — especially if you’re on a tight budget. Apple adds 30% to the subscription price when you sign up through the app, so the website gives you a better deal.

© Lori Corbet Mann, 2025

📌 This month’s posts focus on understanding burnout, because research shows that understanding why we need to take steps makes it far more likely we’ll stick with them. But if you feel you need tools to steady yourself now, I’ve published “In Uncertain Times, Start Here” — a series of posts with some simple but highly effective practices for managing your stress response.

We start with the breath — the only part of your stress response you can shift at will. When you slow and deepen your breath, you send a powerful signal to your entire system: it’s safe, you can rest, you’re not in immediate danger.

Part 1: Developing awareness of the way we breathe naturally — because we can’t change what we’re not aware of.

Part 2: Diaphragmatic Breathing — the foundation on which all calming breathing techniques are built.

Part 3: The science of therapeutic scent — a powerful, layered intervention that interrupts the stress response and supports a shift toward regulation and calm.

Part 4: Three-Part Breath — helps you build up the capacity of your lungs without forcing it.

Part 5: Constructive Rest — a simple and relaxing position that allows your body to release physical tension without strain.

Part 6: This shares the most effective calming breathing technique I’ve learned in 30 years. Simple yet exceedingly powerful — it’s my go-to.

These posts will also help you make sense of what you’re feeling, and find practical ways to recover your balance:

3 Fast-Acting Tools to Help You Tackle Overwhelm Simple, science-backed, therapeutic practices to reset your nervous system, fast.

What It Means to Stay Human When the System Has No Shame How to understand moral outrage, survive moral injury, and protect your capacity to resist.

6 Steps to Recalibrate Without Giving in How to live with clarity and purpose in a system designed to confuse and exhaust you.

Before I turned to creating our current guide, readers found these posts the most steadying. I’ve unlocked each one in the archive so they are all now free for everyone to read.