BREAKING: CIVICUS Has Downgraded US Civic Space. Here's What That Really Means

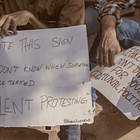

A global watchdog has now branded US civic space “obstructed”. I unpack what it’s seeing on the ground — and how closely that lines up with the six-stage playbook I mapped out six months ago.

📌If you find this work of value, and want to help your civic neighbours find their way to it, please like, comment, and share this post. Each of these small actions helps the algorithm place it in front of others who may need it.

Dear friends

Back in May, I wrote a couple of posts about the direction of travel for protest in the United States, framing it around a six–stage playbook drawn from Russia, India, Hungary, El Salvador and the UK. I argued that the US was already moving through those stages, and that people needed to act as though a constitutional crisis was underway, rather than waiting for some formal declaration.

Today, the global watchdog CIVICUS has released its Global Findings Report for 2025, People Power Under Attack 2025, with a country–specific brief on the United States. The picture they paint is not only stark — it tracks very closely with the trajectory I set out months ago.

CIVICUS has now downgraded the USA’s civic space rating from “Narrowed” to “Obstructed”, noting a sharp deterioration in fundamental freedoms after Trump’s return to office in January 2025. A narrowed rating already signals noticeable constraints, but an obstructed rating indicates a more systematic pattern. The downgrade cites sweeping executive actions, restrictive laws, and aggressive crackdowns on protest, media and dissent.

In other words, what I wrote as a warning in late May has now hardened into international assessment.

In this piece, I want to walk you through what CIVICUS is now saying, and how it lines up with the six stages I described earlier in the year.

If you’ve not yet read these posts, you can find them here:

CIVICUS’ View of The United States

CIVICUS monitors civic space worldwide — by that, they mean the real–world conditions that shape whether you can speak, organise, protest and publish without fear. They score countries from 0 to 100 and place them into five bands: Open, Narrowed, Obstructed, Repressed, or Closed. This year, the US has dropped six points, from 62 to 56, and has been moved into the Obstructed category alongside states such as Hungary, Brazil and South Africa.

In its new brief on the USA, CIVICUS describes a pattern rather than a collection of isolated incidents.

It highlights a militarised response to protest, including the deployment of 700 Marines and 2,000 National Guard personnel to Los Angeles for 40 days in response to demonstrations against aggressive immigration raids. That kind of deployment is presented as part of a wider shift towards using federal force to police civic life.

It notes a sharp escalation in repression of pro–Palestine activism. Students and academics are being suspended, investigated and, in some cases, detained or interrogated at borders. Foreign–born students and faculty are singled out as particularly vulnerable to visa threats, disciplinary processes and professional retaliation for their speech on Palestine.

The brief also records a worsening environment for journalists. Reporters covering protests have faced arrest and physical assault. There are documented cases of border searches, device seizures and prolonged questioning of journalists and lawyers whose work touches on Palestine and protest.

Alongside this, the global findings chapter on tactics of repression notes that between January and April 2025 at least 41 US states introduced bills imposing new restrictions on protests. At federal level, authorities are using the Catch and Revoke programme — a joint initiative of the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Justice and State Department — to deploy artificial intelligence to monitor the social media of thousands of student visa–holders for perceived sympathy with Hamas or other designated groups.

Placed together, these are not random developments. They describe a coherent strategy, one that is very close to what I sketched out in May.

Stage One: From Protest as a Right to Protest as a Threat

In my first piece, I said that the playbook begins with language. Protest is reframed as a threat: to safety, to public order, to the nation itself. The labels shift from “citizens” and “students” to “agitators”, “extremists”, “terrorist sympathisers”. I pointed to how pro–Palestine, racial justice, climate, LGBTQ+ and migrant–rights protests were already being described in those terms.

CIVICUS now underlines how this framing has firmed. Its US brief describes a year of “aggressive crackdowns on free speech and dissent” in which pro–Palestine activism, in particular, is being cast as a security issue rather than a political position.

That narrative work is echoed in other independent documentation. The Brennan Center has shown how Trump and his officials repeatedly characterise targeted foreigners as “pro–Hamas”, “pro–terrorist” or “anti–American”, and how pro–Palestine positions are conflated with support for terrorism in order to justify deportations and surveillance.

I wrote that once protest is successfully recast as extremism, the full counter–terrorism toolkit becomes available against it. What CIVICUS and others are now recording suggests that this is precisely what is happening.

Stage two: Legal Architecture That Criminalises Dissent

The second stage I described was legislative: not a single sweeping ban on protest, but a steady layering of new offences, vague definitions and harsher penalties that turn dissent into a legal minefield.

That pattern has now been confirmed at scale. CIVICUS notes that, in 2025 alone, at least 41 US states introduced new laws to restrict peaceful assembly. These measures include expanded notification requirements, broader liability for organisers, and new criminal and civil penalties for protests deemed disruptive.

All of this sits atop a pre–existing wave of anti–protest bills passed since 2017, many copied from model legislation aimed at protecting “critical infrastructure” such as pipelines and highways, with felony penalties for any protest activity near those sites. What looked, a few years ago, like scattered state experiments has matured into a dense, nationwide patchwork.

In my report, I described how these kinds of technical reforms — often tucked into broader bills and presented as matters of “order” or “safety” — effectively shift the burden of risk onto protesters and organisers. CIVICUS now captures the cumulative effect of these changes by moving the US into the Obstructed category, where legal constraints on assembly are understood as structural rather than incidental.

Stage Three: Expanding Enforcement and Surveillance

The third stage in the playbook is the expansion of enforcement powers. Once laws shift, the machinery of the state begins to treat protest not as a liberty to be facilitated but as a threat to be managed. We see more militarised policing, more surveillance, and a deeper reliance on national–security language.

CIVICUS now cites one of the clearest markers of that shift: the deployment of Marines and National Guard units into a US city to respond to protest. That is not ordinary policing; it is a symbolic and practical escalation.

At the same time, digital surveillance has intensified. CIVICUS’ global findings note that the Catch and Revoke programme in the US uses artificial intelligence to scan the social media of thousands of student visa–holders for content interpreted as sympathetic to Hamas or other designated groups. Independent reporting confirms that this initiative is geared towards identifying “foreign nationals who appear to support Hamas” for visa revocation, drawing on large–scale automated trawling of online speech.

Further reporting describes ICE building a broad social–media monitoring capability, including contracts for tools capable of analysing vast quantities of posts and linking them to real–world identities. Civil–liberties groups have warned that this creates a social–media “panopticon” with obvious implications for protest and dissent.

Months ago, I argued that the counter–terrorism infrastructure built after 9/11 would inevitably be turned further inward — that tools developed for external enemies would be used against domestic movements. The combination of military deployment, mass surveillance and AI–driven visa policing now documented around US protests is a concrete form of that prediction.

Stage Four: Targeting Organisers and Foreign–Born Leaders

The fourth stage focuses on organisers. The logic is simple: if you want fewer protests, you do not need to go after every participant, you simply go after the people who make protest possible.

CIVICUS’ US material now contains several examples that fit this pattern. It highlights the arrest of Mahmoud Khalil, a prominent pro–Palestine student organiser, by ICE agents who claimed that both his student visa and green card had been revoked, despite no public allegation that he had engaged in any unlawful conduct. Trump publicly celebrated his arrest as the first of “many to come”.

The same Brennan Center analysis points out that Catch and Revoke is explicitly framed as a tool to find “foreign nationals who appear to support Hamas or other designated terror groups” via their online speech, and that it is being used to chill participation in First Amendment–protected activity by foreign–born residents.

CIVICUS also documents a wider pattern of targeting those with precarious immigration status, as in cases of academics and activists facing suspension, border interrogation and visa jeopardy after expressing public support for Palestinian rights.

In my earlier posts, I said that the people most exposed would be organisers, immigrants, and those already subject to layered systems of control. I also argued that deportation and visa revocation would be used as tools of political neutralisation, without the need to prove wrongdoing in open court. The record that has emerged since then shows exactly that logic in operation.

Stage Five: Normalising Repression, Especially on Campus

The fifth stage is “normalisation” — the point at which tactics that would once have caused outrage become part of the background. Not every incident needs to be spectacular if, taken together, they create a climate in which repression feels routine.

Here, CIVICUS’ US country brief is particularly telling. It records the Trump administration’s efforts to punish universities seen as insufficiently aligned with its positions, including a sweeping set of demands to Harvard University that tied continued federal funding to changes in governance structures, new reporting duties to immigration authorities, and the dismantling of diversity, equity and inclusion programmes. When Harvard refused, the administration moved to freeze billions in grants and contracts, and even floated revoking its tax–exempt status.

None of this is framed as an outright ban on protest. Instead, it operates as pressure on institutions that provide space and legitimacy for dissent — universities, law firms, media organisations. At the same time, new bills in states such as Texas are designed to weaken protections against SLAPP suits, making it easier to drag critics into expensive litigation.

Taken together, this looks very much like the landscape I said was coming into view: legal changes that appear technical, combined with selective enforcement and financial pressure, all pushing institutions to distance themselves from protest and from those who support it.

Stage Six: The Chilling Effect

The final stage in the playbook is the chilling effect: the point where the law no longer needs to be used in its most extreme form because fear does much of the work on its own.

Evidence of that chill is now widespread. Reporting shows international students learning that visas have been revoked only when they attempt to travel, often with little explanation, and with pro–Palestine protest activity cited as a basis. Academics and journalists have described delaying or cancelling travel to the US after repeated border interrogations linked to their public work on Palestine.

Legal analysts warn that programmes such as Catch and Revoke will inevitably sweep far beyond any narrow definition of “terrorism”, because they are designed to search for broad categories of political speech, and because the administration’s own rhetoric lumps together criticism of US or Israeli policy with “support for terrorism” or “anti–American” activity.

CIVICUS, for its part, now explicitly frames the US downgrade as a response to a “rapid and systematic attempt to stifle civic freedoms that Americans have come to take for granted”. That is another way of describing a chilling effect moving from the margins into the core of public life.

Those are precisely the dynamics I described six months ago: not protest being banned outright, but protest becoming so risky — to your liberty, your visa, your career, your institution — that many people understandably decide to stay home.

So, Was My Forecast Accurate?

No set of predictions is ever perfect — events will always take unexpected turns. But if you compare the six stages I set out in May to what CIVICUS and other monitors are now documenting, the alignment is uncomfortably close.

I argued that:

Protest would be reframed as extremism and terrorism.

Laws would steadily expand to criminalise protest and those who organise it.

Enforcement would become more militarised and more reliant on surveillance.

Organisers — especially immigrants and students — would be targeted early.

Repression would be normalised through institutions, not only through police.

A chilling effect would follow, where protest is not forbidden but largely absent.

CIVICUS’ downgrade of the US to Obstructed, its focus on militarised protest responses, its detailed accounting of legal changes, its documentation of AI-driven visa surveillance, its case studies on pro-Palestine repression on campuses, and its concern about the wider climate for media and civil society all point in the same direction.

So yes — in broad strokes, the trajectory I described then is the one that has unfolded since.

For me, this is not an exercise in self–congratulation. The point of naming a pattern — especially in times like these — is not to be proven right later, but to give people a clearer view of what they are living through while there is still room to act. You now have a clearer picture of the conditions you are living in. When you can see the pattern, and know that it is not “just you”, it becomes easier to decide what kind of action is still possible, and what kind of protection you need.

On Thursday, I am going to put the protest guides I’ve shared directly alongside the CIVICUS findings, stage by stage. You will be able to see exactly what was visible six months ago, what I said would follow, and how closely that now lines up with events. If you want to know whether this publication is giving you commentary or genuine early warning, that is the comparison to read. I hope you’ll join me for it, and that it helps you feel a little less alone in making sense of where we are now.

In solidarity, as ever

— Lori

© Lori Corbet Mann, 2025

📌 If this post was useful, and you know someone else who’s finding things heavy-going, please feel free to share it with them.

If you’d like to make sure you never miss a post, you can subscribe here.

And if you’d like to show your appreciation without commiting to a subscription, you can make a one time contribution below.

Thank you, Lori. Your research, knowledge, experience, and support is a priceless gift. This is terrifying and disheartening to say the least.